Most owners of private businesses think about the value of their businesses from time to time. Business value is not just a measure of accomplishment for an owner-entrepreneur. It is an important factor in planning for the future, whether with regard to business succession, management of personal assets, or estate planning in response to the inevitability of death or disability. Determining value means estimating what a company will sell for. Since the sale of a substantial business is something owners do infrequently, finding the correct answer to the question, “What’s My Company Worth?,” usually requires help from someone accustomed to valuing companies, including in the context of a potential sale.

This document summarizes frequently applied valuation methods, discusses the important difference between market value and investment value, and suggests how accepted valuation methods can be used to enhance value in the event of a sale or reduce value in connection with estate and gift planning.

I. Approaches to Estimating Potential Sales Price

Among a variety of methods appropriate to different circumstances, there are three principal approaches to estimating the potential sales price of a private company: (1) comparison to the company of financial ratios derived from sales of comparable companies and market performance of publicly traded companies in the same or similar industries; (2) analysis of the sales prices of known comparable companies in comparison to the company; and (3) a discounted cash flow analysis based on the expected performance of the company. All three of these approaches (along with any other approach that is relevant) should be used when the owner of a private business is seriously contemplating a sale.

A. Financial Ratios

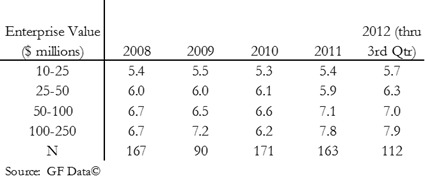

Financial ratios of done deals involving private companies are reported in several proprietary databases, and it is comparatively easy to apply them to a company being considered for sale. Table 1 shows EBITDA multiples for private transactions by financial buyers in recent years, with the number of transactions included in the data presented being shown at the foot of each year’s column.

The multiples shown below are published by GF Data Resources and are derived by them from information provided in confidence by private equity firms in the business of buying and selling private companies in leveraged transactions. Since the underlying transaction data is confidential, it is not possible to compare actual transactions, just statistics derived from them.

Table 1: Total Enterprise Value (EV/EBITDA)

Several observations about the table are worth noting. First, for enterprise values up to at least $250 million, larger companies are worth more than smaller companies and attract higher EBITDA multiples. Second, in years when the stock markets were highly volatile, valuation multiples for private companies purchased by financial buyers were relatively stable. Deal volumes were down substantially in 2009, but valuations did not change much. Third, as stated above, the transactions reported on were by financial buyers. This class of buyer looks for deals all the time, but their ability to execute a deal can be limited by the availability of debt financing which usually makes up a substantial part of the money they use to buy a business. The lack of availability of debt financing is one explanation for the decline in deals reported in 2009. Another explanation is that while prices as a multiple of EBITDA did not decline in 2009, EBITDA declined resulting in a reduction in total value. In some cases owners were unwilling to sell for the lower total values that the pricing ratios implied. Finally, as discussed below, prices paid by financial buyers usually do not reflect the value of synergies that can be harvested when one operating company buys another. A synergistic buyer can afford to pay more.

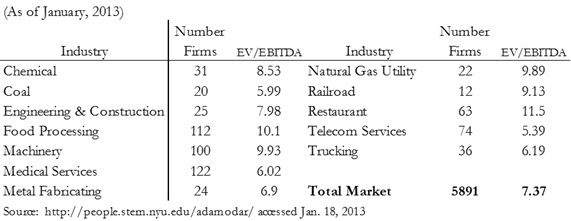

Valuation ratios vary from industry to industry and from public company to private. The ratios shown in the table above are for 100% control of a private company with no separation by industry. The following table shows ratios for minority interests in publicly traded companies in the United States. The ratios are as of January, 2013 and the source is the web site maintained by Professor Aswath Damadoran of the Stern School of Business at New York University.

Table 2: EBITDA Multiple of US Public Firms in Selected Industries

An acquisition of most of the companies whose values are reflected in the table would require a premium price, in the range of 20% to 30%, in order to obtain control.[1] Thus, the total market EV/EBITDA for a control position would be in the range of 8.84 to 9.58. Specific industries carry both higher and lower EBITDA ratios.

In addition to premiums for control (and discounts from control value for minority interests), the valuation literature supports substantial discounts for the lack of marketability of minority interests in private companies. As for control interests in private companies, the control party usually has the ability to sell, but a sale is likely not going to occur without expense or delay. Thus, while control interests of private companies are marketable, they are not as liquid as publicly traded stocks and a liquidity discount should be applied to ratios derived from market values of comparable public companies when such ratios are used to value a control interest in a private firm.[2]

B. Comparisons to Prior Sales of Known Comparable Companies

As noted above, financial ratios from private transactions are available for the purpose of estimating the acquisition value of a private company. Valuations are more reliable, however, if based on substantial data from sales of known comparable private companies, and these are hard to find. Databases frequently contain information from transactions involving an acquisition or divestiture by a public company because, depending on materiality, these have to be reported in SEC filings. PW&Co subscribes to databases providing access to information on specific transactions, but we use this information cautiously. An example of a data base report is attached as Exhibit A. There are no requirements for disclosure of information on the purchase or sale of a private company by a private company and comprehensive deal data on this type of transaction is hard to obtain and often imperfect.

C. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis Based on Expected Financial Performance

Comparable transactions and comparable ratios are important and informative in private company valuations. However, they are backward looking and most people buy and sell based on expectations of what is going to happen in the future. Expectations are heavily influenced by history, but a business owner who believes that the best days of his company are in the near future is not going to be satisfied with a price that reflects only the past. In addition, a forward looking valuation permits buyers and sellers to consider the synergies available from a business combination. Possible synergies include increases in value as a result of (i) a larger combined company, (ii) diversification of customers, markets and other business elements, (iii) economies of scale resulting in greater operating efficiency (perhaps at the expense of layoffs of long term employees), and (iv) improved utilization of fixed assets through reduction of redundant equipment and facilities.

The considerations described in the preceding paragraph can be captured in financial projections for future years and both buyers and sellers should prepare pro forma projected financial statements (to include income statements, balance sheets and cash flow statements) spanning three to five future years and reflecting expectations of future performance. Most middle market companies will want help performing this type of analysis because most companies do not do it frequently. The exercise is important, because those performing the analysis are, in effect, trying to demonstrate that 2 + 2 > 4, and this is a neat trick if it can be accomplished. However, prudent buyers should remember that an entire book has been written on how expected synergies have frequently failed to be realized.[3]

Exhibit B is an example of a discounted cash flow valuation analysis (DCF).

Each of the three valuation methods discussed here has its champions. The Delaware Chancery Court and McKinsey & Company favor discounted cash flow analysis. Recent decisions of the United States Tax Court tend to favor comparable company analysis. Investment bankers and many private business owners tend to start with ratio analysis. Our view is that every relevant method should be employed and reliance placed on the method or methods that seem closest to the facts and circumstances.

II. Market Value vs. Investment Value

The preceding discussion has focused on the “market value” of a private company, the price that an owner desiring to sell can reasonably obtain for his company. Market value assumes that a party is motivated to sell, that another party is motivated to buy, and that there is a price satisfactory to both at which a deal can be done.

“Investment value” of a company is the value of the company to one party or another and may be more or less than market value.[4] For example, the owner of a successful private business likely receives more in annual income, perquisites of ownership, and cash distributions than can be replaced by reinvesting after tax proceeds of a sale in publicly traded securities. Such an owner will sell only if the owner has a compelling need to sell, such as to solve a management succession problem or to obtain diversification of investment assets, thus reducing risk.

One way to avoid a forced sale at a price below “investment value” is to engage in long term planning for management succession and diversification of financial assets while passing on ownership and control to future generations. As a result of discounts for lack of control and marketability, gifts and bequests to family members of minority interests in a private business can substantially reduce gift and estate taxes, especially if structures such as family limited partnerships are employed. Family limited partnerships can be used in tandem with trusts to pass ownership on to more than one younger generation. In addition, diversification of assets and resulting reduction of risk can be accomplished through the accumulation of wealth outside the company. Finally, a plan for succession in leadership should be put in place by promoting a family member with proven ability or selecting a proven manager from within the Company or from the outside.

III. Conclusion

In our view, every substantial private company should apply standard valuation techniques periodically to determine market value and investment value. These values should be used in long term planning for the future of the company and its owners so that succession, diversification and gift and estate tax issues can be addressed before they become urgent. It takes a number of months to sell a private company. Longer sales periods and reduced sales prices are associated with lack of preparation. The highest valuations are obtained by sellers who are under no compulsion to sell but are prepared to do so if the right deal comes along. Such sellers frequently enjoy the good fortune that comes from encountering someone who wants to buy a business more than the seller wants to sell.

Please download the full White Paper to view additional Exhibits.

[CF WP1.0 r2]