This issue of The Bank Shot gives expert insight on the current regulatory environment as well as an update on the M&A marketplace.

In “What to Ask Washington,” Larry C. Lavender identifies issues that community bankers should bring up with candidates for federal office.

In “A Walk Down Memory Lane…2015 Bank M&A Scorecard,” we review the 2015 merger marketplace from a long-term perspective.

What to Ask Washington

Porter White & Company is pleased to present the insights of Larry C. Lavender. Larry was Chief of Staff for the Republican minority on the House Financial Services Committee during the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act (which was opposed by all of the Republican members of the committee) and subsequently Chief of Staff for the Republican majority on the Committee after the 2010 election. Larry is an expert on the regulation of community banks and other financial enterprises and is currently a governmental relations consultant in Washington and Alabama.

We asked Larry to identify the major policy issues facing community banks that should be presented to candidates for federal office in this election season.

As the 2016 election season starts, it is imperative that community bankers raise with candidates for federal office questions regarding the candidates’ positions on critical issues impacting their institutions. Rather than restating a few sound bites and bullet points, I have tried to tie my suggestions to a serious policy discussion produced by a relevant arm of the Government of the United States. (Yes, some parts of the government do good work.) To give you my conclusion in advance, I believe that community banks should seek relief from the most onerous regulations mandated by current law, because as a group they are unlikely to do major harm to our financial system, and reduced regulation of community banks will in general do more good than harm. Community bankers should seek the support of aspiring federal office holders in pursuing this objective.

The Dodd-Frank Act includes a requirement for the regulators and government agencies to promulgate 390 rules to implement its provisions. As of the end of the third quarter of 2015, 307 rules have been finalized or proposed, leaving 83 as yet undrafted. In recognition of the burden this massive regulatory expansion would impose on business and the public, Congress included in the Dodd-Frank Act a provision for the Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) to study this regulatory burden each year and report to Congress on its findings. In a document dated December 31, 2015, the GAO issued a report entitled “DODD-FRANK REGULATIONS, Impacts on Community Banks, Credit Unions and Systemically Important Institutions.” Among other matters, the report purports to examine “…the possible impact of selected Dodd-Frank Act provisions and related rules on community banks and credit unions.”

Not surprisingly, the report found that community bankers and regulators differed in their assessment of the costs and other impacts associated with the Dodd-Frank Act. As the report says, “… community banks, credit unions, and industry associations GAO interviewed cited an increase in compliance burden associated with these rules. Some of these industry officials also reported a decline in specific business activities, such as loans that are not qualified mortgages, due to fear of litigation or not being able to sell those loans to secondary markets.”

Regulators, on the other-hand, “… told us that it is still too early to assess the full impact of Dodd Frank Act rulemakings on community banks and credit unions, and while they have heard concerns about the increase in compliance burden, they have not been able to quantify compliance costs.”

Even though the Dodd-Frank Act purports to exempt community banks from many of its provisions, anyone with regular contact with the managers of small banking institutions will be well aware that they believe they have been subjected to dramatically increased compliance costs and significantly restricted investment opportunities. That cost/earnings squeeze is particularly galling to bankers who universally believe their segment of the industry contributed virtually nothing to the financial collapse that gave rise to the Dodd-Frank Act.

Many observers believe that one of the groups most responsible for the financial crisis in 2008 was the credit rating industry which issued indefensible ratings long after it became apparent the underlying mortgages did not support the credit worthiness of the securities into which they had been accumulated. One of the most paradoxical effects of Dodd-Frank is that the altogether ineffectual provisions intended to address the short-comings of the clearly culpable credit rating agencies are wreaking serious collateral damage on the completely blameless community banks.

Dodd-Frank required that credit ratings be eliminated as a standard to determine whether an investment is “investment grade.” Federal agencies were tasked with reviewing their regulations and replacing reliance on credit ratings with standards of credit worthiness each agency deems appropriate. Those revised regulations now provide that for any investment, an insured depository institution must determine that the probability of default by the issuer is low and the full and timely payment of principal and interest is expected. The rules governing that determination are complex, detailed and include analyses of the institution’s risk profile.

Every banker knows that reasonable, prudent due diligence is necessary for any investment and a comparison of the financial crisis losses suffered by community banks as a group versus larger institutions shows clearly the smaller banks were far more careful and aware of their duty to perform that function than the largest institutions. Community bankers have long operated under the requirements summarized as the three Cs of credit – Character, Capital and Capacity. They didn’t need the Dodd-Frank Act to tell them they must to be certain they will get their depositors’ money back on time when they make an investment. The problem for small banks is that the way they evaluate an investment is vastly different from the process decreed by regulatory bureaucrats.

The new rules require a process that is far beyond the capability of most community banks. There were approximately 6,200 FDIC-insured institutions with less than $10 billion in assets in 2015. Of those, nearly 3,800 had assets of less than $250 million. Those 3,800 simply do not have the staff and expertise to comply with the new standards being promulgated, at least not with confidence they will not be subject to examiner over-reach or investor law suits. These smaller banks have more employees per $1 million in assets than the larger institutions. Allocating already tight budget dollars for sophisticated investment advice exacerbates that disparity and is a totally unwarranted burden.

At a time when the small manufacturer borrower base is shrinking, the qualified mortgage rules make housing loans more difficult and CFPB auto lending restrictions eat into that market, community banks will be faced with an ever narrowing operating margin between escalating compliance costs and fewer places to deploy their depositors’ money. Finding investment vehicles that will provide a reasonable return and meet the new standards of credit worthiness without costly and burdensome vetting will be a continuing challenge for community bankers.

To conclude, Congress should amend the Dodd-Frank Act to do the following:

- define in statutory language a special regulatory classification for “Community Banks” to include banks below a stated asset size, indexed for inflation;

- make a finding that individually and as a group Community Banks are not systemically important to the stability of the U. S. financial system;

- provide for exemption of Community Banks from specific provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act deemed by Congress to be inapplicable to financial institutions that are not systemically important;

- require the reconsideration of all regulations applicable to Community Banks and the exemption from such regulations of Community Banks absent substantial documented evidence that the regulation is necessary to protect the FDIC insurance fund or to pursue a statutory objective unrelated to the safety or solvency of an individual bank.

When it comes to regulating the economy of the United States, less is usually superior to more, and this is particularly true when it comes to the Dodd-Frank Act and community banks. We need more elected leaders committed to deregulation, and community bankers should work to get this commitment.

A Walk Down Memory Lane…2015 Bank M&A Scorecard

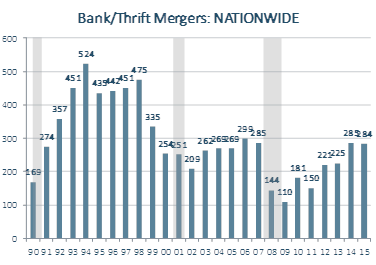

This past year saw 284 deals nationally (essentially flat from 2014) and 63 deals regionally (up from 56 in 2014). Deal pricing in 2015 was also up slightly over 2014. Does this mean we are in an M&A boom? To answer the “boom” question, we believe it is insufficient to compare 2015 solely with 2014 or even the last five years. Rather, we think it is necessary to travel back in time and look at 2015 in the context of the last quarter century.

At First Glance, Deal Activity Looks Ho-Hum

In purely raw numbers, while 2015 was flat (U.S.) or slightly up (Southeast) over 2014, it still trails the 1990’s when there were routinely over 400 deals nationally (1994 saw 524 deals!). This implies that deal activity, while markedly up following the Great Recession, is “off the pace” historically.

Note: All chart data courtesy of SNL Financial or the FDIC. Grey bars represent recessions (Jul90-Mar91; Mar01-Nov01; and Dec07-Mar09). Southeast: AL, AR, FL, GA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA and WV.

Upon Second Look, Deal Activity is ROBUST

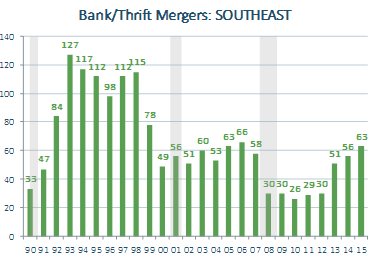

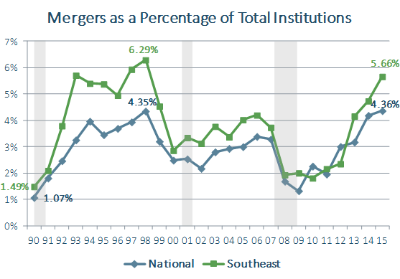

However, simply viewing 2015’s raw deal count against the 90’s is not an “apples-to-apples” comparison because there are less than half the banks today than there were in the early 90’s. In other words, we need to look on a relative basis to see if 2015 was depressed by historical standards. We did this in the following chart by dividing the number of deals in a given year by the total number of institutions at December 31st of the prior year.

Upon second glance, 2015 deal activity in relative terms was higher nationally (4.36% of total banks) than any year going back to 1990 and the highest since 1998 for the Southeast (5.66% of total banks).

Note: Grey bars represent recessions (Jul90-Mar91; Mar01-Nov01; and Dec07-Mar09). Percentages were calculated by dividing mergers in a given year by total institutions at Dec. 31 of the prior year. Southeast: AL, AR, FL, GA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA and WV.

What About Deal Pricing?

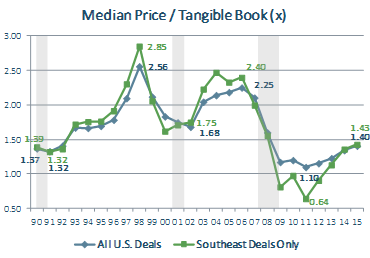

Does this mean the boom is really here? The answer is “partially.” Our preceding chart established that, yes, relative deal activity in 2015 was robust by historical standards. However, activity must be separated from pricing to get a full answer. When looking at pricing in bank mergers, 2015 paled in comparison to most of the last quarter century.

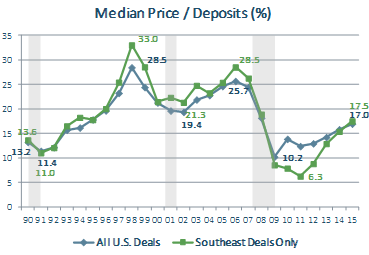

The following charts show that the nosedive in pricing around the 2001 recession was pronounced, but that it was nowhere near as severe as the Great Recession (Dec07 to Mar09). Deal pricing in 2015, while up over the 2009-14 period, has only returned to early 1990’s levels.

Note: Grey bars represent recessions (Jul90-Mar91; Mar01-Nov01; and Dec07-Mar09). Southeast: AL, AR, FL, GA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA and WV.

Comparing the post-2009 recession period with the two previous post-recession periods reinforces that we have a long way to the “boom” from a pricing standpoint.

Pricing following the 1990-91 recession topped out in 1998 at Price/Tangible Book of 2.56x (U.S.) to 3.00x (Southeast) and Price/Deposits of 28.5% (U.S.) to 33.0% (Southeast).

Pricing following the 2001 recession topped out in 2006 at Price/Tangible Book of 2.25x (U.S.) to 2.40x (Southeast) and Price/Deposits of 25.7% (U.S.) to 28.5% (Southeast).

Comparatively, pricing in 2015 were a median Price/Tangible Book of 1.40x (U.S.) to 1.43x (Southeast) and a median Price/Deposits of 17.0% (U.S.) to 17.5% (Southeast). Demonstrating the severity of the latest (and “greatest”) recession, we are six years into the recovery yet 2015 prices were clearly well off the pace of the previous two post-recession periods.

Another interesting observation from the pricing charts is the “boom or bust” pricing of Southeastern deals in relation to deals nationally. Deals in the Southeast have shown “higher highs” than deals nationally (e.g., 1998) but have also demonstrated “lower lows” (e.g., 2011).

The Jury is Still Out

Our journey back in time has yielded conflicting results. On one hand, 2015 saw robust deal activity (in relative terms) by historical standards. On the other hand, deal pricing in 2015 fell far short of historical standards, specifically post-recession pricing. Without robust activity AND pricing, it is probably premature to declare an M&A “boom.” If 2016 sees higher deal prices in conjunction with continued high relative deal activity, we can likely say the verdict is in and declare the “boom” upon us.

Please visit our Community Bank website to learn more how Porter White can help meet your bank’s M&A and other needs.

Please contact Michael Stone, CFA (205.252.3681; michael@pwco.com) for more information on the bank M&A marketplace.