Individual Retirement Accounts (IRA’s) offer years of tax-deferred growth but can be double-taxed (under both estate and income tax law) at the owner’s death. Individuals should assess their goals and circumstances in planning how to maximize the after-tax value of their assets. The short answer to the question, “What to do about the IRA Double Tax Hit,” is the following:

- Don’t let your tax professionals forget about the IRD deduction

(it is one of the most missed deductions[1]), and - Consider designating your children (or charity) as a beneficiary.

For the full details, please continue reading.

I. Overview of the Double Tax Hit

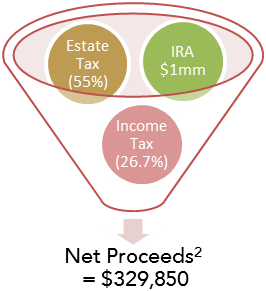

Individual retirement accounts provide a great way for people to accumulate investment assets on a tax-deferred basis. They can, however, create issues for estate planning purposes. If an IRA is paid to its owner’s estate, then 100% of the IRA asset is included in the value of the estate and potentially subject to estate taxes. This means that an IRA account can be subject to estate tax at rates currently as high as 35%, and going to 55% on January 1, 2013. In addition, the IRA asset will also be taxed at income tax rates of 35%, although the taxable amount may be reduced by the estate tax payable as a result of including the IRA asset in the estate. The risk of double taxation is something that IRA owners should be aware of and plan for.

On the other hand, if an individual is named the beneficiary of the IRA, income taxes on IRA distributions are deferred. Estate taxes are still payable, unless the beneficiary is a spouse (or perhaps a charitable institution).[2]

Under current law, on January 1, 2013, the estate tax rates and exemptions will return to 2001 levels, which will make estates in excess of $1 million ($2 million for married couples) estate taxable at marginal rates up to 55%. A greatly reduced estate tax exemption amount means that many more people need to consider estate tax planning issues, especially with regard to IRAs.

In this commentary, we address the question of whether it is better for someone with an expected taxable estate to accelerate withdrawals from their IRA during their life and pay income tax, or leave it to their beneficiaries. What is best for each individual requires some advanced planning and consideration.

II. Question and Assumptions

The issue addressed here is whether IRA owners should withdraw their full IRA account balances during their retirement or take minimum IRA payouts and leave almost all of their IRA to their beneficiaries. In order to answer this question, one must evaluate the applicable estate and income tax consequences of each option.

For purposes of this discussion, we assume that the IRA Owner in question (Owner) is 70 years old, with a spouse (Spouse) roughly the same age, three children in their mid-to-late forties and grandchildren. Owner expects to have an estate taxable under the estate tax provisions of the Internal Revenue Code (Code) and other investment assets sufficient to cover debts, expenses and estate taxes. Owner is already making the maximum allowable annual gift to the children and their spouses from other assets. We also assume for purposes of this analysis that future tax-deferred gain earned on assets held in an IRA will offset the impact of future income taxes paid on the required minimum distributions from the IRA.

III. Discussion

To answer the question of whether to draw down the amount in the IRA during the Owner’s lifetime, we must compare the costs of a full distribution of IRA assets to the Owner versus costs incurred in preserving the IRA for the Owner’s beneficiaries. The major costs here involve the income tax on IRA distributions and the estate tax on a transfer at death of the IRA. However as we shall see, a commonly forgotten benefit often available in an estate taxable death transfer of an IRA is an income tax deduction called the IRD deduction provided under §691(c) of the Code. (The IRD deduction is equal to the estate tax paid with respect to the value of the IRA in the Owner’s estate. It is a deduction against income, not a tax credit, so it provides only a partial recoupment of the estate taxes paid on the IRA assets in the Owner’s estate.)

A. Accelerated Withdrawal by IRA Owner

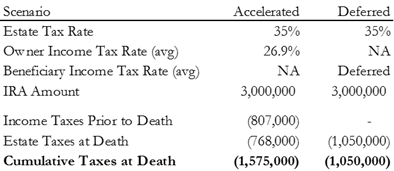

If Owner and Spouse were to withdraw the full amount of the $3 million IRA over ten years, they would receive about $300,000 in income each year (disregarding growth over the term). The only other income the taxpayers currently receive comes in the form of dividends on investments, so it is unlikely that they would pay ordinary income taxes beyond the 33 percent tax bracket (as the 35 percent bracket does not begin until $379,151 of income).

The federal income tax is determined using a system of graduated rates. As total income earned in a year climbs through certain dollar ranges, the income dollars within each range are taxed at increasingly higher rates. For example, while the last dollar of $300,000 will be taxed 33 percent, the first dollar of that amount is only taxed 10 percent. Therefore, most of the $300,000 IRA distribution would be income taxed today at rates below 33 percent, producing an average income tax rate on $300,000 of 26.9 percent. Assuming the same rates would be applicable over the ten year distribution period, Owner and Spouse will pay a total of $807,000 in income taxes on the $3 million IRA distribution. The remaining $2,193,000 after income tax will then be exposed to the estate tax (currently 35%) when both Owner and Spouse have died, unless the proceeds are disposed of during their lives by gifting, spending, converting or some combination of all three. Since Owner and Spouse are already using other assets for those purposes, they likely will not be able to dispose of much of the after tax IRA distribution proceeds. If the IRA distribution proceeds cannot be properly transferred out of their names, 35 percent estate taxes on the leftover amount will total $768,000, leaving $1,425,000 to pass to their heirs.

B. Give IRA to Children – Deferred Distribution

If Owner keeps the IRA intact as it is, the full amount will be included in his estate for estate tax purposes and taxed accordingly. Assuming all estate tax exemptions are used up on other assets, the estate tax rate on additional assets would currently be 35 percent. Therefore, if Owner holds the $3 million IRA intact until his death, the estate would pay $1,050,000 in estate tax.

Assuming the estate tax was paid out of other estate assets (not the IRA), the beneficiaries would receive $3 million in an IRA. They will owe income tax on distribution amounts as distributions occur. However, the beneficiaries also receive four benefits that reduce the tax cost of this option: 1) the income tax on the IRA growth that occurred during Owner’s lifetime continues to be deferred until distribution of that growth, 2) the income tax on post-death IRA growth is also deferred until it is distributed, 3) the period over which IRA post-death distributions must be made may be extended to the life expectancies of the beneficiaries allowing for more income tax deferred growth, and 4) a deduction against taxable income attributable to IRA distributions may be available to a beneficiary. This deduction is equal to the estate taxes paid by the estate of the Owner with respect to the IRA assets passed to a beneficiary.

IV. Income in Respect of a Decedent (IRD)

Any deferred and untaxed income (including IRAs) that a decedent had a right to receive at their death is considered “income in respect of a decedent” (IRD) for the taxpayer who receives that income after the decedent’s death. The beneficiary of an item of IRD does not get a stepped-up income tax basis and therefore the amount received is income taxable to the beneficiary just as it would have been to the decedent if he or she had lived to collect it. IRA distributions are one type of IRD.

To help reduce the double tax effect when an IRA or other types of IRD are both income taxed and estate taxed, the beneficiaries receiving the IRD should get a deduction against IRD when received equal to the amount of the estate tax paid and attributable to the item of IRD. Therefore, if the estate pays an estate tax of $1 million on IRA assets, then the beneficiaries can claim an IRD deduction of $1 million against IRD income. With estate tax rates being 35 percent or higher, the IRD deduction will likely be substantial on any IRA included in a taxable estate, so it is critical that the IRA beneficiaries are both aware of the IRD income tax deduction and use it.

Two criteria must be met: first, if the estate paid estate tax as a result of the IRA being included in the estate, then the beneficiaries are entitled to an IRD deduction to the extent of the amount of the estate tax attributable to the IRA; and second, the beneficiaries must actually claim the deduction on their income tax returns. Based on comments in the relevant professional literature, the IRD deduction is rarely claimed, because beneficiaries generally do not know about it.

V. Conclusion

As shown in the figure below, we conclude that in many cases it is not better for an IRA owner to take accelerated distributions. Likely, a better strategy is to defer the payment of taxes over time. The key assumptions for this result are that 1) the IRA beneficiary will spread out the distributions over his or her remaining lifetime, 2) sufficient liquidity exists to pay the estate taxes attributable to the IRA, and 3) the value of tax-deferred growth offsets the cost of the income taxes paid over time by the beneficiary.

(Note that under the Deferred scenario, the Beneficiary will also have available a deduction with respect to IRD of $1,050,000, worth about $368,000 at an assumed 35% tax rate.[3])

The inherent value of any tax-deferred investment is in its long-term growth potential, and the cost deferred is, for the most part, tax. Therefore any discussion of what to do with an IRA must examine the best way to extend the period of tax-deferred growth while spreading withdrawals out at the lowest possible rate of tax. Based on the assumptions made here, we conclude that the best way to get assets out of an IRA with the lowest possible cost is by passing the IRA on to children (beneficiaries) who can both get and use the IRD income tax deduction. Every individual’s circumstances are different so not all will reach the same conclusions. The underlying principles still apply.

[2] The net proceeds assumes a deduction for estate taxes paid is taken in calculating the income tax due; if no deduction is taken, net proceeds are $183,000.

[3] We assume a 26.9% average income tax rate for Owner but a 35% rate for Owner’s children, the Beneficiaries. Because Owner lives on investment income rather than ordinary income, any ordinary income generated in Owner’s name will start out in the lowest bracket. However, Owner’s children live off of ordinary income and already earn enough to be at or near the 35% bracket.

This document is intended to raise issues for consideration by friends and clients. A number of simplifying assumptions have been made and details omitted for purposes of analysis. Consequently, readers are encouraged to seek competent tax counsel and not rely solely on any of the statements made herein.

Under requirements imposed by the IRS, we inform you that, if any advice concerning one or more U.S. federal tax issues is contained in this communication (including any attachments), such advice was not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purpose of (1) avoiding penalties under the Internal Revenue Code or (2) promoting, marketing or recommending to another party any transaction or tax-related matter addressed herein.

[WMC 1]