When we manage client accounts, we typically devise asset allocation policies (or portfolio models) that specify the amount (in percentage terms) that we will try to hold of each investment option in the account. As time goes by, the investment options will inevitably have different returns and the holdings will almost never match the model. To bring the holdings back to policy, we need to sell portions of the funds that performed better than average and buy the ones that did worse. We call this “rebalancing.”

Many academics and practitioners have tried to figure out the best rules to rebalance a portfolio. Sometimes, we like to crunch the numbers ourselves to see if we can learn anything. In the exercise we describe below, we find that there are potential gains from rebalancing at the right time, but these gains are not large. We conclude that rebalancing is important as part of a disciplined approach to investing but should not be expected to add significant value to a portfolio.

I. Narrowing the Problem

Like almost everything investment-related, rebalancing can get complicated quickly. For this commentary, we are going to narrow the problem to what an individual might face inside their 401k account. Rebalancing inside of most 401k plans does not involve any trading costs or have any tax implications. None of the investments we consider have redemption fees either.

When the investment options have significantly different risk characteristics (i.e., stocks and bonds) other factors and constraints come into play, such as investor risk tolerances. Our exercise will only have stock mutual funds with expected returns that are fairly similar to each other.

For this exercise, we use returns from the 7 year period starting April 1, 2007 and ending March 31, 2014. This covers the end of the last bull market, the great recession and the recent recovery. We also assume that rebalancing is “all or nothing” – i.e., either all positions are rebalanced at a time, or none are rebalanced. Our analysis is inherently limited by these assumptions and constraints.

II. A Few Scenarios

A. Simple Option: Do Nothing

Sometimes the best thing for most investors is to do nothing. We looked at what the equity model portfolio in our 401k plan would have done if we had put $100 in the account and then did nothing. During this time period, the investor would have watched this $100 fall to $46 and then recover and grow to $142. At the end of the period, the holdings have significantly deviated from the original policy. Even worse, one holding that was above its policy by a significant amount (i.e., it had earned significantly above average returns) had returned to a level more in line with the original policy. The return over this seven year period would have been 5.13% per year on average – not a great return for an all stock portfolio!

B. Periodic Rebalancing

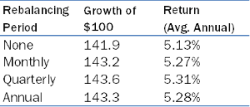

Another option would be to set up rebalancing on a monthly, quarterly or annual basis. The returns under these rebalancing scenarios are summarized in the following table.

While rebalancing does seem to have added a dollar or so to the account, there doesn’t appear to be a clear winning rebalancing strategy using these simple rules.

C. Crystal Ball Approach

While the future is uncertain, the past has already happened and we have the data to analyze it! We can determine when would have been the right time to rebalance a portfolio over this time period. With the benefit of hindsight (and some powerful excel add-ins to solve an optimization routine), we found the answer.

It turns out that an investor should have rebalanced five times over that seven year period to achieve the best results. These optimal rebalancing dates were at the end of July 2007, February 2008, October 2008, September 2010, and August 2013. The portfolio result would have been better than any other approach to rebalancing. The portfolio would have grown to $146.1 with an average annual return of 5.56%. The result is almost 0.43% per year better than doing nothing.

III. So What Now?

Unfortunately, we don’t have the ability to predict the future (and if we did, we could do better than just rebalancing our accounts!). Even more disappointing, knowing the right answer (for the past 7 years) and analyzing it did not give us a clear answer of why those five times were the best to rebalance, further limiting our ability to predict the future. The portfolio was rebalanced when the positions varied to different degrees. Rebalancing this stock mutual fund portfolio also didn’t significantly change the volatility of returns or the magnitude of the losses incurred.

From this simple analysis, we can draw a few conclusions:

- Knowing when to rebalance requires the ability to predict the future, as far as we can tell.

- Don’t rebalance too frequently; the best answer is to rebalance no more than twice in every year and sometimes not at all.

- The potential benefits of rebalancing an all stock portfolio are likely fairly small, particularly when compared to trading costs and potential taxes in other account types.

These conclusions do not imply that we do not think rebalancing a stock mutual fund portfolio is important. We think that it is an important part of a disciplined approach to investing. The potential gains from rebalancing equity portfolios are hard to achieve and likely not worth the potential expenses involved. The most important action is to design a good portfolio, and then stick with the plan through market cycles.

While this analysis applies only to all stock mutual fund portfolios and is based on the simplifying assumptions above, future commentaries will look at portfolios that include bonds as well.

Important Notes:

(a) Annualized returns are geometric (compound) averages.

(b) The S&P 500 (or any index) is not “investible.”

(c) Historical performance results for investment indexes, or categories, generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction or custodial charges or the deduction of an investment-management fee, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results.

(d) Economic factors, market conditions, and investment strategies will affect the performance of any portfolio and there are no assurances that a portfolio will match or outperform any particular index or benchmark.

(e) Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.