With the re-election of President Obama, additional Medicare taxes on capital gain income will almost certainly go into effect in 2013. The “Bush Tax Cuts” are also set to expire and it is possible that the highest capital gains tax bracket will revert to 20% from its current 15% level. Many investors are asking whether they should realize capital gains this year at a lower rate so as to avoid likely higher taxes on capital gains in the future. The answer to this question turns on a number of factors relating not only to taxes but also to future performance of the economy and markets as well as individual circumstances. In this commentary, we will examine some of these factors and their implications for investors.

I. Sources of Increased Taxes on Capital Gains

There are presently two ways that capital gains taxes can increase: an already enacted Medicare surtax and a return to the capital gains tax rates in effect prior to the Bush tax cuts.

A. Medicare Surtax

The 3.8% Medicare surtax under the Affordable Care Act will come into effect January 1, 2013.[1] This surtax applies to income that exceeds specific thresholds ($250,000 for married joint filers). For individuals, the 3.8% surtax is imposed on the lesser of (a) net investment income for the tax year or (b) modified adjusted gross income greater than the threshold. Net investment income includes interest, dividends, annuities, rents, capital gains, trading of financial instruments and other passive activity income.

B. Capital Gains Tax Brackets

At the beginning of the Clinton administration, the highest tax bracket on capital gains taxes was 28%. This rate was lowered to 20% by the end of the second Clinton term. During the Bush administration, the highest capital gains tax bracket was lowered to 15%. The Bush Tax Cuts were extended two years ago and are set to expire at the end of 2012. The Obama administration advocates letting the highest capital gains tax bracket revert to 20%. Some op ed writers are advocating even higher rates.[2]

II. Assumptions

It is very difficult to give general advice to any taxpayer because of the many complexities in the tax code that require analysis on a case by case basis. Realizing capital gains has the potential to affect other deductions. Realizing losses can also have different impact on taxable income based on individual circumstance. In our analysis, we have made a number of limiting assumptions, too numerous to fully list. Our objective is to raise issues, not provide individual tax advice.

For our scenarios, we assume the following:

- An investor has a holding with a current market value of $200,000 and an unrealized, long-term gain of $100,000.

- The investor can sell this holding and reinvest in a comparable investment avoiding the wash-sale rule.

- The investor can absorb capital losses.

- All capital gains are taxable at the highest marginal tax bracket.

- Taxes paid reduce the amount invested.

- State taxes on all income are 5%.

- Highest federal tax bracket on capital gains, including Medicare surtax, is 23.8%.

- Both state and federal taxes are deductible against each other leading to a current com-bined effective tax rate of 18.5% and a potential future combined tax rate of 26.4%.

- Time value of money and the investor’s total investment capital are not considered.

III. Three Scenarios

To help understand the implications of the anticipated increase in the capital gains tax, we consider three scenarios relating to the future return on the investment described in our assumptions.

A. No Change in Investment Value

If an investor has an investment that is unlikely to appreciate and has the choice of realizing a gain when tax rates are lower as opposed to when tax rates are higher, then the best choice is likely, “Sell Now.” It is difficult to conceive of circumstances that would lead to a different decision, although the gnomes who draft the tax codes frequently surprise us.

B. Decline in Investment Value

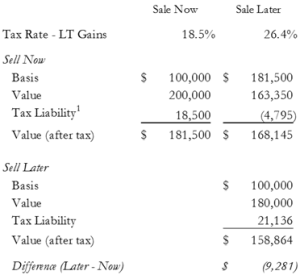

If the investor realizes gains now, taxes of $18,500 will be payable, reducing the net amount in-vested going forward from $200,000 to $181,500. If the investment suffers a 10% loss before it is subsequently sold, the decline in investment will be partially offset against realized capital losses (assuming that there are other capital gains against which losses can be offset).

If the investor chooses to sell later, then more capital will remain invested and the dollar loss will be higher. The realized gains will be lower, but the taxes paid on the gains will still be higher. The net amount is a decrease of over $9,000 in value after tax for the person that chooses to sell later. This conclusion is derived by comparing (i) an immediate sale at the lower rate, followed by a second sale at the higher rate after 10% depreciation, with (ii) no sale immediately and a sale at the higher rate after 10% depreciation.

The results from the scenario using market interest rates in July 2010 from our previous commentary are copied for convenience below.

Table 1: Scenario B: Decline in Investment Value of 10%

(1) The “(Tax Liability)” becomes a “Tax Asset” if the loss can be offset against other capital gains. If not, the “Difference (Later – Now)” is ($4,486).

C. Increase in Investment Value

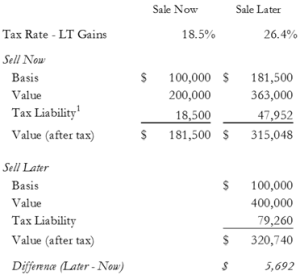

One of the hesitations that many investors have in “Selling Now” is that they have to pay taxes sooner. By paying taxes now, the investor loses the potential return on the taxes paid. In a rising return environment, this opportunity cost can offset the value of taking advantage of a lower tax rate.

To illustrate this concept, we consider the scenario where the investment grows by 100% in the period after capital gains tax rates go up. We compare (i) an immediate sale at the lower rate, followed by a second sale at the higher rate after 100% appreciation, with (ii) no immediate sale followed by a sale at the higher rate after 100% appreciation. In both cases, there will be additional capital gains taxes due. However, the investor who chooses to “Sell Later” has more in-vested earning a 100% return, so the after tax value is over $5,000 greater than in the case of the investor who chooses to “Sell Now” and again “Later,” as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Scenario C: Increase in Investment Value of 100%

There is some return where an investor is indifferent between realizing gains now or later. For the combined 26.4% tax rate, the breakeven return is 58.2%.

IV. Fourth Scenario – Don’t Sell (Ever)

Investors should keep in mind, however, that capital gains are not taxable inside of an estate, and it can be beneficial to use appreciated securities for charitable giving purposes. Both of these treatments could change in the future and are subject to restrictions under current tax law, but these options should also factor into any investor’s decision to sell now or later.

V. Conclusion

Based on our analysis, it appears to make sense to realize gains now before tax rates go up, except for the high expected return, long-term investor. We caution, however, that there are a number of assumptions underlying this conclusion and inevitable uncertainties about the future that affect a decision. The ultimate impact on an increase in a portfolio’s value due to this “tax-management” is small compared to the amount of return the investor’s portfolio generates through exposure to markets.

[2] Rattner, Steven. New York Times. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/24/more-chips-for-tax-reform/?hp. Accessed November 26, 2012.

This document is intended to raise issues for consideration by friends and clients. A number of simplifying assumptions have been made and details omitted for purposes of analysis. Consequently, readers are encouraged to seek competent tax counsel and not rely solely on any of the statements made herein.

Under requirements imposed by the IRS, we inform you that, if any advice concerning one or more U.S. federal tax issues is contained in this communication (including any attachments), such advice was not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purpose of (1) avoiding penalties under the Internal Revenue Code or (2) promoting, marketing or recommending to another party any transaction or tax-related matter addressed herein.

[WMC 3]