A lot of companies approach us to raise capital. The reasons are varied – product development, plant expansion, company acquisition, working capital –and the sources of capital available to a company depend on the size, lifecycle stage, and future prospects of the company. While new capital may come with restrictive covenants and other levels of intrusiveness, the largest cost to a company (and its existing investors) is the new investors’ cost of capital – the expected return a company must provide new investors to entice them to invest in a company instead of a different investment.

The cost of capital is the expected rate of return that investors require in order to invest in a company with a given risk profile. This means that the company must give up enough future cash flow or ownership to make the investment worthwhile to the investor. Each investor is willing to accept a different level of risk, in exchange for a commensurate return. However, when investor behavior is aggregated in the private capital markets, a picture emerges.

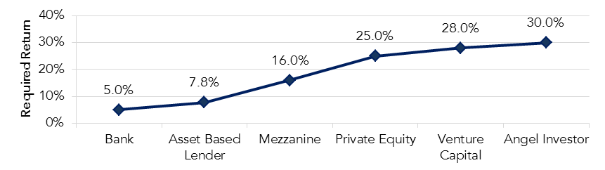

The annual Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project provides an interesting look at how capital market participants price risk. Within each category reported by Pepperdine, the cost of capital is identified based on specific risk metrics (size of loan, size of company, or stage of company). The chart below shows the required rates of return for different market participants: banks/senior lenders ($5M loan size), asset based lenders ($5M loan size), mezzanine lenders ($5M loan size), private equity groups ($5M EBITDA), venture capital firms (early stage investments), and angel investors (seed investments).

Private Capital Markets Required Rates of Return

Source: Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project, December 2013.

As shown above, banks require the smallest return, in exchange for the most security (first lien on assets). Equity investors on the other hand are willing to take substantially more risk if there is significant up-side potential. In our experience, venture capital firms, private equity groups, and angel investors are often not enticed to invest in start-up companies with expected returns of only 20-30 percent; rather, they invest in multiple start-ups with far higher return potential in anticipation that most start-ups will fail and a few will be highly successful.

When a company starts to think about raising new capital, timing is often critical. Sometimes the answer is to wait a few months before seeking new investors. A new product might have just launched or a large service contract might have been signed recently, but a few months of actual data showing positive results make future revenue assumptions much more believable and less risky. If a company is burning through cash and its development cycle is delayed, there may not be an option to delay the financing; however, consider raising only a bridge round to complete the product development cycle. Once there is a successful product to sell, the investment becomes less risky. Lower risk translates into a lower cost of capital and a higher valuation, leaving higher returns for existing investors.