For many people nearing or planning for retirement, the key question is: How do I replace my paycheck? Will my retirement savings be sufficient? How much can I withdraw each month? How many assets do I need to cover the basics?

An investor can get some answers to these questions by obtaining quotes on annuities from insurance companies. However, while purchasing an annuity from an insurance company provides protection against longevity (assuming the insurance company is able to meet its obligations), it also limits financial flexibility in the future if circumstances change.

Investors can structure their own “paychecks for the future,” using their assets to purchase U.S. Government bonds, with maturities matching future “paydays.” Structuring a hypothetical portfolio of this type can be very helpful in answering questions like:

- How much does it cost, in a lump sum, to replace my current income?

- How much of my savings should be allocated towards fixed income (bonds) to meet my expected basic living expenses or other investment goals if I do not want to take any risk?

I. Creating Your Own Annuity

To create your own paycheck, you need to decide on two things: 1) how much money you want and 2) when you want it. For our example, assume that you plan to retire in 2015, and you want a known “income” for another 25 years. You have basic living expenses that you believe will be covered by a $10,000 per month ($120,000 per year) pre-tax[1] income in addition to your social security. You also expect your basic living expenses to go up about 3% per year for inflation.

We now have all the information we need to create your annuity. That is, you need $120,000 per year available January 1, starting in 2015 and growing by 3% per year for the next 25 years. All we have to do now is find the investments that get you there.

II. Selecting the Investments

Since we want as much certainty as possible that you will receive future paychecks, we will choose payments guaranteed by the U.S. Government. Although there is some probability that the U.S. Government could default, it is the highest credit quality available. Also, we will choose something called zero-coupon bonds. That way, you will not have to worry about reinvestment rates before you need the money.

In contrast to many “regular” bonds, a zero-coupon bond has, as the name implies, no current coupons. Rather, all interest is accrued and paid at maturity of the bond. You get the benefit of the interest by paying a lower price upfront. For example, a 10-year regular bond with a 4% coupon and face value of $1,000 sold at a yield of 4% will cost you $1,000 to purchase. In contrast, a 10-year zero-coupon bond sold at a yield of 4% will only cost you $673 to purchase, but will pay you back $1,000 when it matures.

So, if you want to receive $120,000 in 10 years, you would have to purchase 120 zero-coupon bonds for a total cost of $80,760, assuming the bonds are priced to yield 4%. In our analysis of the entire portfolio, we will also adjust the $120,000 with an inflation factor over time.

III. The Entire Portfolio

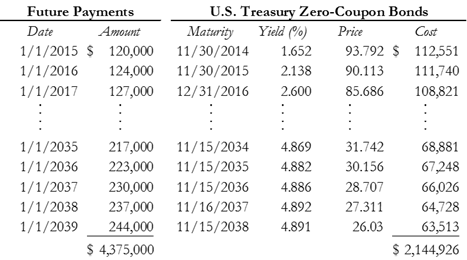

Our next step is to “map” out all the future payments you want to receive, account for the cost of living adjustment, and estimate the price of the entire portfolio. This type of bond portfolio is referred to as a “bond ladder” and is shown in the table below.

The prices shown above are as of January 6, 2011 and are subject to change.

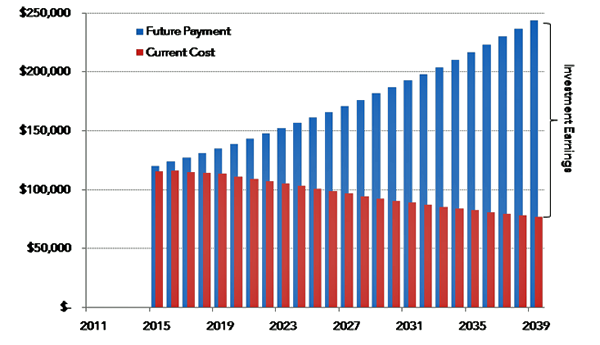

Your first paycheck of $120,000 occurs on January 1, 2015, and the zero-coupon bond that matures closest, but prior, to that date is one that matures on November 30, 2014. The cost of that $120,000 face value bond is $112,551. The last paycheck occurs on January 1, 2039 and the amount has been increased to $244,000 to account for the 3% annual cost of living adjustment. The cost of that paycheck is $63,513, and so on. We do this until we have all of the 25 future payments accounted for, and as shown in the table, the current estimated cost of that portfolio is approximately $2.1 million. The following chart shows future payments as well as current costs for each future payment.

We have now created our own “annuity equivalent,” which will generate an income of $120,000, starting in 2015, increasing by 3% per year.[2] Further, these individual securities can be held in your own account, and the payments are guaranteed by the U.S. Government.

IV. Risks and Benefits

The risk of creating your own annuity to live on in retirement is that you outlive your assets. On the other hand, if you purchase an annuity and you die before your expected actuarial life, you are giving up some of your assets.

One of the benefits of purchasing an annuity from an insurance company is that you embed a longevity insurance policy in your annuity. While actuarial life assumptions may not apply to you individually, they tend to hold for the pool as a whole. If you die early, someone in the pool who lives longer benefits from that and vice versa.

If you are willing to take the risk that you might outlive the assets you set aside to live on in retirement, creating your own annuity can have several benefits and provides financial flexibility. First, you are not giving up any value if you die before the end of your actuarial life. By creating your annuity from bonds, any remaining assets will pass to your heirs when you die.

Second, you are not taking on the risk that the insurance company fails to make good on its promise if you purchase direct obligations from a bond issuer, but you do take on the risk that the issuer of the bonds fails to meet its obligations. Although American International Group (AIG) was bailed out by the federal government and many insurance companies enjoy an implied guarantee from the government, it is not explicit. The government did let Lehman Brothers fail even though this created chaos in the marketplace. If you purchase individual bonds, they are direct obligations of the issuer, such as the U.S. Government.

Finally, holding the bonds yourself, rather than letting the insurance company hold them for you, provides financial flexibility as opposed to having purchased an annuity. In the event of unexpected cash needs, if you hold individual bonds, you can quickly sell bonds to meet those needs. This, of course, involves market value risk, and if interest rates have risen, you may lose principal in order to meet those cash needs. On the other hand, if you have purchased an annuity, your only option would be to borrow against the annuity.

Also, if you feel the need to convert to an annuity at a later time, you can always do that if you hold bonds, although your life expectancy and actuarial life changes as you grow older. The bonds are a natural hedge against annuity pricing since the market value of your bonds will be inversely related to interest rates. That is, the value of the bonds will fall if interest rates rise and vice versa. The cost of purchasing an annuity will also vary inversely with interest rates, and the cost of an annuity will fall (rise) as interest rates rise (fall). so that the cost of purchasing an annuity will move in the same direction as the market value of the bonds.

(There is also a risk that you can lose your bonds if they are not kept in a safe place. Do not ignore the mechanics of custody.)

V. Extending the Analysis

So far, we have discussed what it costs to replace a certain level of income, but the analysis can be incorporated into the important decision of how to allocate investments between stocks and bonds. Most investors have several different savings goals. For example, providing for your own living expenses may have higher priority than providing money for children or grandchildren, such as for college, housing, etc., which in turn may have higher priority than charitable causes.

The picture below illustrates a problem facing many investors: investment goals usually exceed current assets. This condition is shown in the chart below as “investment gap.” For investors who do not want to take any risk on a given savings goal, the amount that should be reserved for that expense can be estimated with the “paycheck” analysis discussed here.

For example, an investor with a portfolio of $5 million and estimated future living expenses of $120,000 per year, who wants risk-free provision for those particular expenses, he or she should place at least 43% ($2,144,926 divided by $5,000,000) of the portfolio in bonds. How the remaining 57% should be allocated depends on the investor’s risk and returns preferences.

VI. Conclusion

As investment managers, we help our clients decide how much risk to take to reach their investment goals. The benefit of the method we have shown here, creating government-guaranteed “paychecks” for certain expenses, is that it allows investors to plan for to achieve minimum financial goals using a low risk structure, and then gradually increase risk and expected return to achieve other goals.

[2] Note that the 3% inflation rate is an assumption. Inflation may be higher or lower. [IMC 6.1]